REMEMBERING THE IRISH POTATO FAMINE

The Irish Potato Famine, also known as the Great Hunger, began in 1845 when a fungus-like organism called Phytophthora infestans (or P. infestans) spread rapidly throughout Ireland. The infestation ruined up to one-half of the potato crop that year, and about three-quarters of the crop over the next seven years. Because the tenant farmers of Ireland—then ruled as a colony of Great Britain—relied heavily on the potato as a source of food, the infestation had a catastrophic impact on Ireland and its population. Before it ended in 1852, the Potato Famine resulted in the death of roughly one million Irish from starvation and related causes, with at least another million forced to leave their homeland as refugees.

Between the years 1845-1849 many of our Irish ancestors made the difficult decision that the only way to survive the Great Famine was by emigrating to distant lands where an unknown but hopefully better future awaited them. There simply wasn’t enough food in Ireland to feed all the mouths, so our ancestors scattered to far off corners of the globe – not only to England, Scotland and Wales, but to America, Canada and Australia. This it allowed for a few to stay in Ireland in the hope of surviving.

The ocean that parted them prevented families seeing each other for years on end, if ever again, how they must have longed for one another over the years. Illiteracy – due to a lack of available education in Ireland – prevented most of them from even writing letters to each other.

Over the subsequent generations, their descendants forgot the names of their great-grandparents and even the names of their ancestral villages.

There were often more than a dozen family members sharing a small cottage with their farm animals. The floors were of beaten earth and dried sheepskins were hung over the windows to cut down on the drafts that blew right through the house.

Land records showed that the tenants rented the houses (everyone rented from the English) with a garden, an office (AKA a barn), a cowshed, a piggery, and a bog.

Some people would ask why the Irish would bother to record bogland in an official record. To many it would seem like a useless swamp. But to our Irish ancestors, it was a valuable source of fuel.

Prelude to Famine

While the potato had seemed like the answer to a growing population’s prayers when it first arrived in Ireland, by the early 1800’s warnings began to grow about over reliance on a single source of food. A significant proportion of the Irish population ate little other than potatoes, lived in close to total poverty and were rarely far from hunger. >A typical tenant farmer had barely half an acre on which to grow all the food for a family. Potatoes were the only viable option with such a small landholding.

At least those with tenancies, small as they were, had the certainty of shelter and some food. Homelessness was common, many people lived in makeshift mud cabins or slept outdoors in ditches. Work was in short supply forcing labourers to travel the country in search of employment, surviving on what they could forage, get by way of charity or steal.Life expectancy was short, just 40 years for men, and families were large, with many mouths to feed. The gap between living and dying, even in a good year, was perilously narrow.

In 1836 a report from the Parliamentary Select Committee on the Irish Poor concluded that more than 2.5 million Irish people, more than a quarter of the population, lived in such poverty as to need some kind of welfare scheme. Poor law unions were established to provide work houses where the most impoverished would be fed but these were wholly inadequate even before famine stuck and completely overwhelmed when it did.

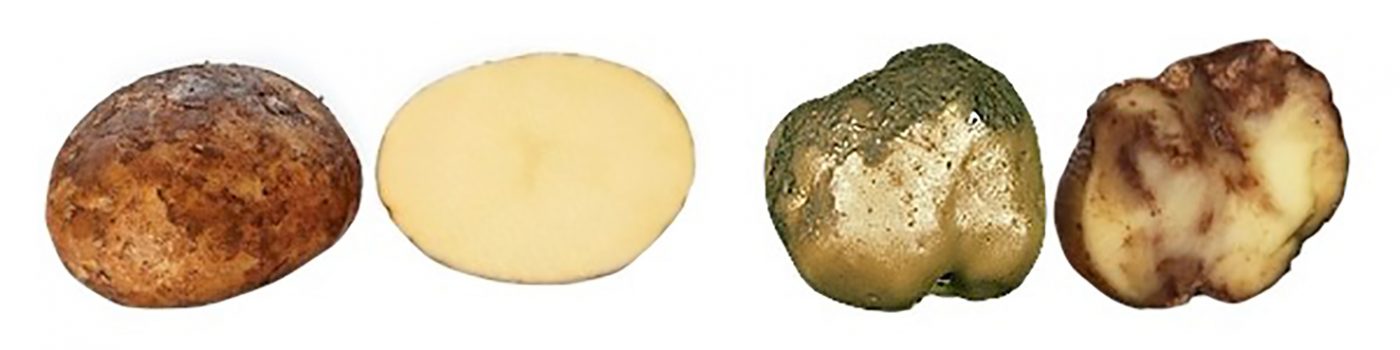

Rotten Potatoes

The disaster began in earnest in 1845 when the potato crop was destroyed by infestation with the fungal disease Phytophthora Infestans, better known as Potato Blight.

In August of 1845, after three weeks of rain and fog, Irish farmers watched in horror as the stalks and leaves of their potato plants began to turn black. The stench coming from these blackened, drooping plants was wretched.

Families rushed to get the potatoes out of the ground to save what little was left around the blighted rot at the centre of each one. They trimmed the pieces that were usable from around the edges, wondering how they would survive the winter and what they would use as spuds to start the next year’s crop.

This devastating disease rotted the potatoes in the ground, rendering entire crops inedible and obliterating the primary food source for millions of people.

The Starving Years

Children were sent into the fields to search the mounds of dirt for any potatoes that may have been overlooked. They sometimes returned with only wild mushrooms or nettles for a thin soup.

During the famine, many Irish folks ate half-cooked potatoes — when they could get potatoes at all. Half-cooked potatoes took longer to digest so they seemed more filling and they were called “potatoes with the bone in them.”

What was a mother to do when her milk had dried up and her baby was dying? She may get desperate enough to kill their last chicken to make a little broth. It may help for a few days.

By 1846, farmers planted what they could in the spring but once again at harvest time the potato crop was struck with blight.

The English provided work for Irish men, digging ditches or building roads. But many were already too weak for such heavy labour and died trying to provide for their families.

When the man of the house died, the women and children often went to the workhouses or poorhouses that had been set up by the English rather than face starvation.

While some landlords allowed their tenants to retain grain crops for food and reduced their tenants’ rents or even waived them, others were remorseless.

Other landlords could have done little even if they had wished to, as they too lost everything. Their tenants could neither pay rent nor work, thus the output of their land plummeted, and their income dried up. Many were forced to sell their land for what little money they could get and leave the country.

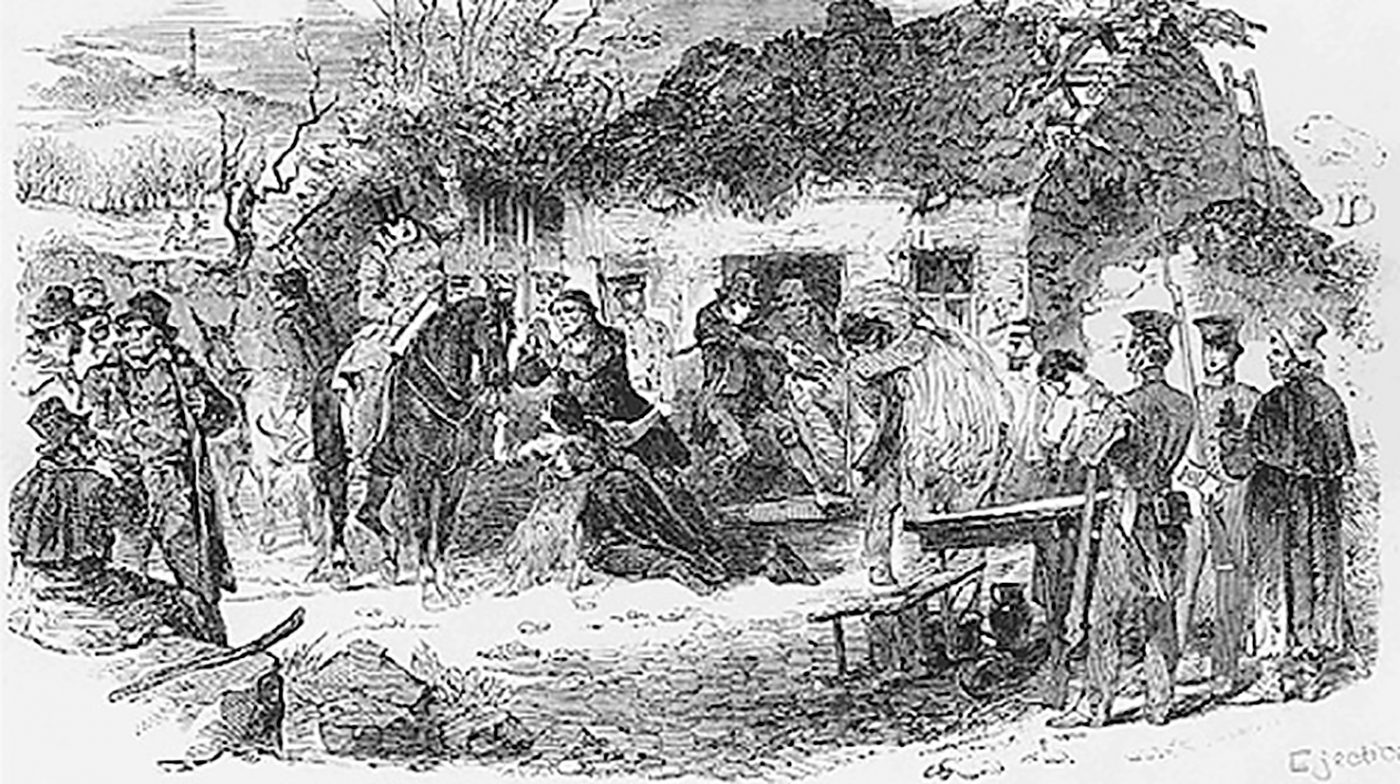

More than a quarter of a million labourers and tenant farmers were evicted between 1845 and 1854 and more than that number simply walked away from their homes, never to return, rather than face certain starvation. Thousands of evicted families roamed the country in search of food.

More than 1 million people died of starvation or disease – to put that in context, an equivalent loss in the US today be almost 40 million people. More than 2 million others emigrated over a six year period. Whole families, even whole villages, left en masse.

Those who could afford to leave were considered to be the lucky ones, though they may not have felt particularly fortunate – many of them travelled on dangerous and overcrowded ships on which considerable numbers died.

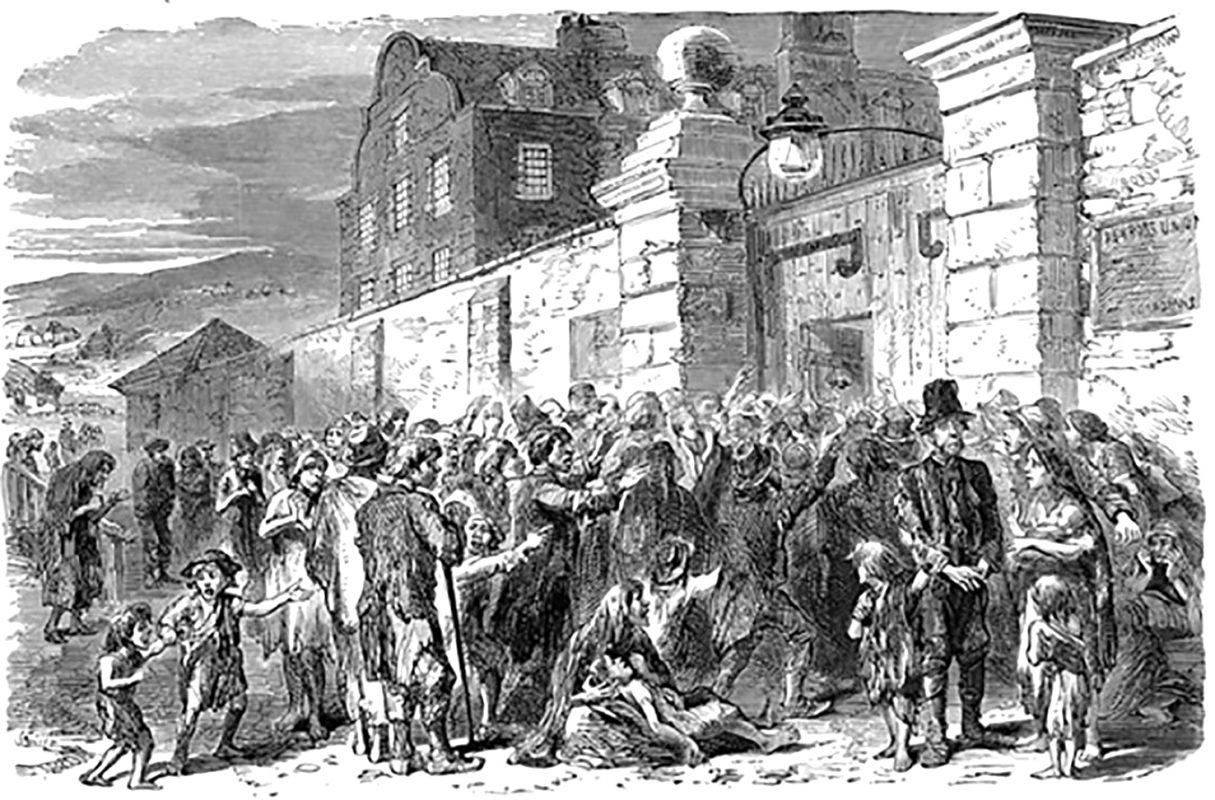

The Irish Famine Workhouse

Life inside an Irish workhouse was purposefully brutal in order to discourage all but the truly desperate from entering.

Sometimes entire families entered the workhouse together. Males and females were separated, only to see each other during Sunday worship services, if at all.

Those who arrived at a poorhouse were usually at death’s door due to starvation, dysentery, and fever. The overcrowded conditions didn’t help the situation and disease ran rampant.

Inmates – as poorhouse residents were called – were set to work breaking stones or crushing bones to produce fertilizer.

Those who died at the workhouse were sometimes buried in a mass grave.

Others were put in a wooden coffin and rolled out to the burial ground on a cart. After the coffin was placed in the ground, a false bottom dropped and the body fell through to the earth. The wooden coffin could then be lifted out and reused.

Surviving the Irish Famine

The English sent some Indian corn or maize to those still striving to survive outside the workhouses, but it was poorly ground and caused abdominal pain and diarrhoea.

In 1847, Britain passed the Extended Poor Law, a tax that shifted the cost of the maintenance for poorhouses and the feeding of the starving masses from the British government to the Irish landowners.

The effect was that many English landowners decided to evict their Irish tenant farmers. Between 1847 and 1851, the eviction rate rose by nearly 1000%.

To further encourage the tenant farmers to leave, their homes were sometimes knocked down as the families stood by and watched.

Some English landowners allowed their Irish tenants to live on the land rent-free, but this caused them to eventually go broke.

Others provided their Irish tenants with free passage on ships bound for America, Australia, or Canada. This freed up the land for English cattle to graze.

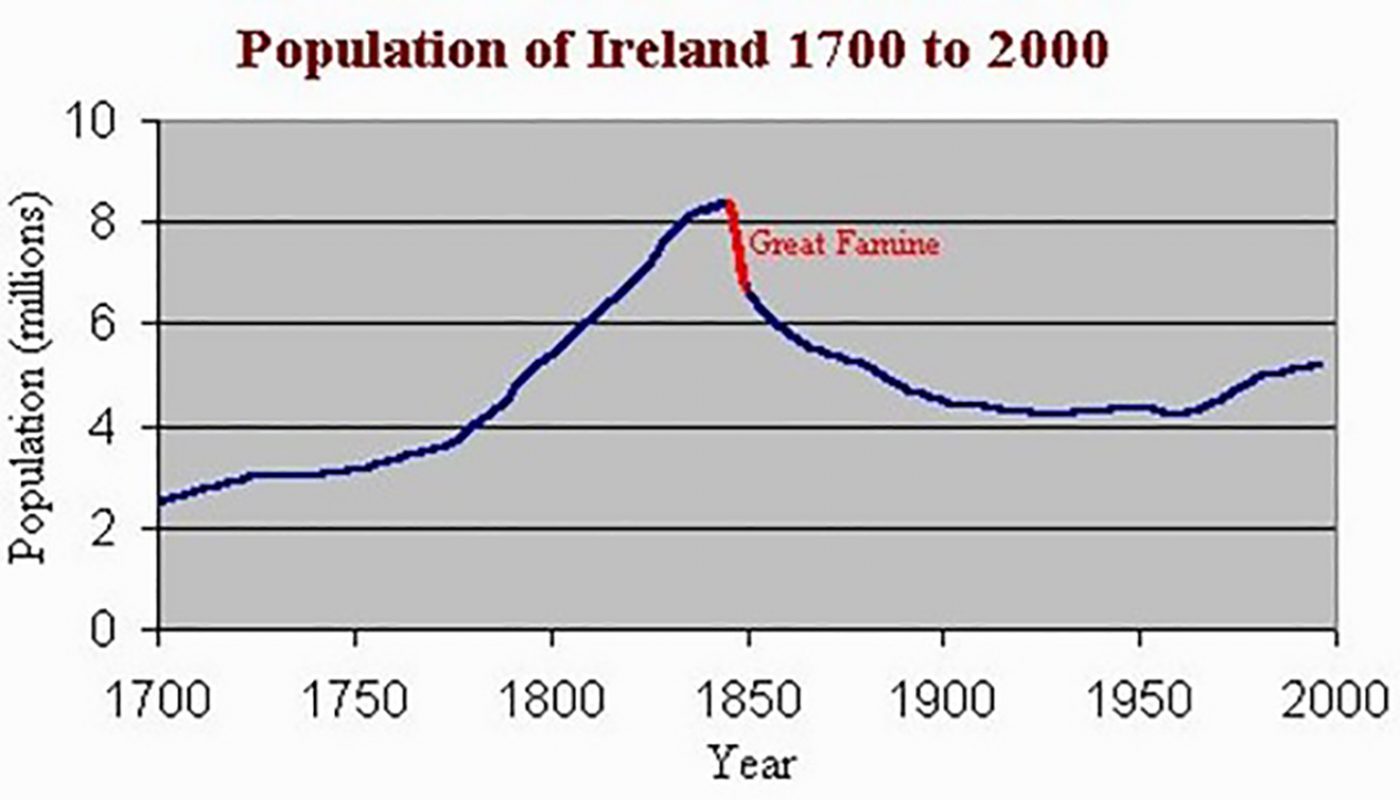

Prior to the Irish potato famine, the population peaked at about 8.2 million. A decade later, the population had dropped to about 6.5 million. Death and emigration accounted for the decline in nearly equal proportions.

Today there are nearly 5 million people in Ireland, while there are an estimated 55 million people worldwide who can trace their ancestry back to the Emerald Isle.

Irish Famine Victims Remembered

But during the Irish famine, the deceased were often piled into mass graves by the thousands, without ceremony, prayers, or good-byes.

But today, in many places across Ireland mass gravesites have now been marked with a single stone in memory of those who suffered and died during the Great Famine.

There are now more than 100 memorials to the Irish Famine worldwide.

One of the most striking memorials is a set of bronze sculptures in Dublin created by Rowan Gillespie to memorialize the Irish Famine emigrants. It features skeletal-like men, women, and children dressed in rags boarding a “coffin ship”.

Starving in the Midst of Plenty

The famine was not really a famine at all.

Ireland, then as now, was a country capable of producing large quantities of food, and continued to do so throughout the famine years.

Only a single crop, the potato, failed. No other crops were affected and there were oats and barley being produced in Ireland throughout these years. But these were considered ‘cash crops’, produced for export and owned not by those who worked in the fields but by large landowners. Food exports continued virtually unabated even as people starved.

William Smith-O’Brien, a wealthy land owner from Dromoland Castle who was sympathetic to the plight of the poor, observed in 1846:

“The circumstances which appeared most aggravating was that the people were starving in the midst of plenty, and that every tide carried from the Irish ports corn sufficient for the maintenance of thousands of the Irish people.“

In Cork in 1846, a coastguard officer, Robert Mann, travelled the county and reported seeing innumerable starving and desperate people and then…:

“We were literally stopped by carts laden with grain, butter, bacon, etc. being taken to the vessels loading from the quay. It was a strange anomaly“

Instead of retaining crops and other food which was already being produced in Ireland, cheaper Indian corn was imported in various efforts at relief.

This corn was regarded with suspicion by the Irish who looked on it as animal feed and had no idea how to prepare and cook it properly. Being accustomed to a diet of potatoes, they had great difficulty digesting this tough grain. Many who tried it suffered terrible pain – some even died – though eventually they learned how it should be prepared in order to be more digestible.

However official attempts to provide relief, in the form of imported corn or in any other form, were sporadic, short lived and inadequate for the numbers who were in need. Of the effective help that was provided during the famine little came from the government in London.

Although some efforts were made in 1945 by the English prime minister Robert Peel to both reduce exports of grain and increase imports of cheaper American corn, these were not continued by Lord John Russell, who succeeded him in 1846.

Russell was an enthusiastic supporter of the prevailing economic doctrine, that of ‘laissez-faire‘ – the belief that government must not interfere in the economy. Charles Trevelyn, who was secretary of the Treasury in England and had responsibility for famine relief, had an even less sympathetic attitude to the starving Irish:

“The only way to prevent the people from becoming habitually dependent on Government is to bring the food depots to a close. The uncertainty about the new crop only makes this more necessary“.

There were some government relief efforts: workhouses were given additional resources, though nothing approaching what they needed.

The Famine Comes to an End

By 1852 the famine had largely come to an end other than in a few isolated areas. This was not due to any massive relief effort – it was partly because the potato crop recovered but mainly it was because a huge proportion of the population had by then either died or left.

During the years of the famine, between 1841 and 1851 the Irish population fell from over 8 million to about 6.5 million, and with mass emigration continuing in the subsequent decades it was down to 4.5 million by the turn of the century.

This rapid and dramatic loss of population is still taking its toll right up to the present time and Ireland is certainly the only country in Europe and possibly the only one in the world with a smaller population today than it had in 1840. It set in train a pattern of emigration that persists to this day and is the reason why there are vastly more people of Irish descent living outside Ireland that in it.

Not everyone viewed the loss of so many lives as a calamity, as the preface to the Irish Census of 1851 makes clear:

“…we feel it will be gratifying to your Excellency to find that the population has been diminished in so remarkable a manner by famine, disease and emigration between 1841 and 1851, and has been since decreasing, the results of the Irish census of 1851 are, on the whole, satisfactory, demonstrating as they do the general advancement of the country. “

Disaster or advancement, a less populous Ireland was again in a position to feed itself.